Who really wins or loses from Proposition 13?

Last week, Trulia issued a report headlined, “California homeowners saved more than $12.5 billion in property taxes last year because of Proposition 13, with longtime residents in more affluent cities receiving the biggest breaks.”

The two statements in that headline are half right, but like most claims about Prop. 13, they don’t tell the whole story.

The $12.5 billion figure assumes that properties would be reassessed each year at market value, as they were before Prop. 13 passed in 1978. But it also assumes that the tax rate would be fixed at 1 percent statewide, rather than set by local governments, as property taxes were before Prop. 13.

If Prop. 13 didn’t exist, the actual “savings” could be higher or lower than $12.5 billion, depending on where local governments set tax rates in response to property values and revenue needs.

Before Prop. 13, “when market values increased, local governments tended to reduce their property tax rates. Similarly, when property values declined, local governments increased their property tax rates,” a recent report by the state’s Legislative Analyst’s Office said.

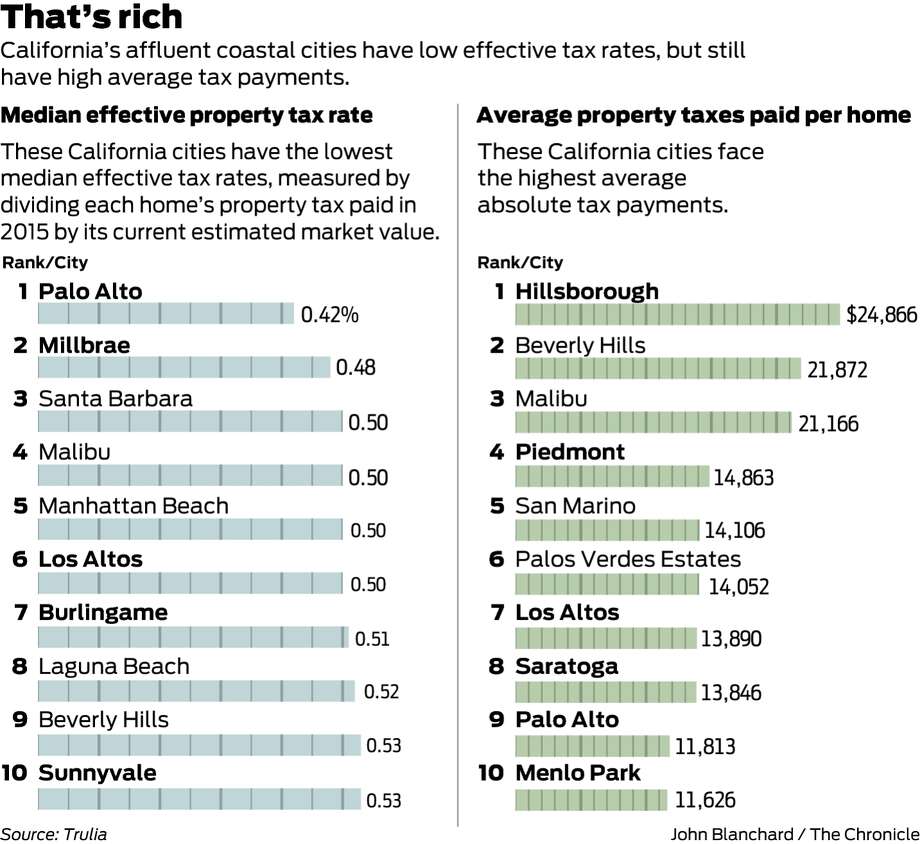

It’s also true that residents in cities with expensive homes get the biggest benefits, measured by their effective tax rate — what they paid in property taxes divided by the home’s current market value. What the Trulia report failed to mention is that property owners in affluent coastal cities also pay the highest property taxes, on average.

The real disparity created by Prop. 13 is not so much city to city. It’s the disparity between similar homes in the same neighborhood that receive essentially the same services but pay vastly different taxes, depending on homeowner tenure.

Property taxes are determined by multiplying a property’s assessed value by its tax rate.

Before California voters approved Prop. 13, homes were assessed each year at their current market value. Each city, county, school district and other local agency set its own rate. The average combined rate was 2.67 percent, according to the state report.

Voters approved Prop. 13 at a time when rampant inflation was pushing property taxes so high that some homeowners could not afford to stay in their homes. It did three things to prevent that.

It set a uniform rate of 1 percent statewide and gave local government agencies the same pro-rata share of property tax revenues they got before Prop. 13.

It also rolled each property’s assessed values back to its 1975 market value and said that henceforth, properties would be reassessed only when sold, generally at the purchase price. After that, the assessed value could go up by the inflation rate, but not more than 2 percent per year (plus the value of new construction, such as a room addition or major remodel). When the home was sold again, the process would start over.

Finally, it required a two-thirds vote for any special taxes levied by local governments.

Including local voter-approved taxes, the average property tax rate in California is now 1.14 percent. But the effective rate — property tax as a percentage of current market value — varies widely.

Homeowners in expensive coastal cities such as Palo Alto and Los Altos, where median home values exceed $2 million, pay effective tax rates under 0.5 percent, while households in inland areas, like Beaumont and Arvin, where home values are under $265,000, have effective tax rates of more than 1.3 percent, Trulia said in its report.

This “cross-city variation” is a result of price appreciation and share of longtime residents, Trulia said. The more a home appreciates, the lower its effective tax rate becomes. The lower the rate, the more incentive there is to stay put. (Indeed the state report found that the percentage of properties that turn over each year has declined from 16 percent in 1977-78 to only 5 percent in 2014-15.)

So cities with a lot of highly appreciated homes and long-term homeowners tend to have lower effective tax rates. Cities with a lot of housing growth tend to have higher rates because a larger percentage of homes have been assessed at current market values.

Although high-price coastal cities have low median effective rates, when homes there turn over, the new owners face exorbitant tax bills — upwards of $20,000 a year on a $2 million home.

Upon request, Trulia provided me with the average 2015 tax payment for all California cities with more than 10,000 people. Not surprisingly, some cities with the lowest median effective tax rates had the highest average tax bills.

For example, the median effective tax rate in Palo Alto is 0.42 percent, lowest of any city. But the average tax bill in Palo Alto last year was $11,813, the ninth-highest of any city. Hillsborough had the state’s highest average tax payment, $24,866.

It’s important to remember that all property taxes stay within your county. They are divided up between your county, city, school districts and special districts.

“If you pay property taxes in Palo Alto, you are paying for services in Palo Alto,” said Carolyn Chu, co-author of the legislative analyst’s report. “The issue is really that there is a lot of difference in what people are paying on a parcel-by-parcel basis.”

Some critics, such as economist Christopher Thornberg, say Prop. 13 is “shockingly regressive” because those who have accumulated the most wealth in the form of home equity are taxed the least.

The state report confirmed that “higher-income Californians own more homes and own homes of higher value and, therefore, receive the majority of the total dollars of tax relief provided to homeowners by Proposition 13.”However, it also found that “substantial differences occur even among property owners of similar ages, incomes, and wealth.” Looking at Bay Area homeowners ages 45 to 55 years with homes worth $575,000 to $625,000 and incomes of $80,000 to $90,000, it found that their property tax payments in 2014 ranged from $1,350 to $7,500.

Even with Prop. 13, property taxes remain the second-largest source of government revenue after the personal income tax. In 2014-15, they raised $55 billion, the state report said.

The Trulia report “attempts to portray winners and losers under Prop. 13,” said Jon Coupal, president of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association. “We would argue that even new homeowners are very much winners. First and foremost, they benefit from a very low rate,” of just over 1 percent, compared with 2.6 percent before Prop. 13. Despite the low rate, “because property is so expensive, property taxes are still very high in this state.”

Source: San Francisco Chronicle

Kathleen Pender is a San Francisco Chronicle columnist. Email: kpender@sfchronicle.com

Twitter: @kathpender